Flying to New Heights

By Kegan Gill

On January 15th, 2014, my life changed drastically. I was a F/A-18E Super Hornet pilot in VFA-143, The Pukin’ Dogs, stationed at Naval Air Station Oceana. Just before my flight, my friend Fisty and I joked how it would be a bad day to eject, as there was a sixteen foot, thirty-five-hundred-pound, great white shark named Mary-Lee directly under the airspace I would be utilizing that day. Fisty used the shark tracker application to find GPS tagged sharks, which helped keep things light around the squadron. The last few weeks in Virginia Beach had been unseasonably cold, so I was wearing a dry suit under my flight gear that day. After some air-to-air refueling, my flight lead and I had some spare fuel and time, so we set up for one versus one Basic Fighter Maneuvering, BFM, about fifty miles offshore over the Atlantic Ocean, directly above Mary-Lee. BFM is what most people think of when they think of what a fighter pilot does: a couple of jets trying to shoot each other down in a dogfight.

Dogfighting was one of my favorite skillsets, along with raging through a canyon on a low-level flight or dropping ordnance utilizing pop attacks in high threat, Close Air Support, CAS. The Super Hornet is a jack of all trades, who needs to be capable of performing a wide variety of roles as well as land on an aircraft carrier. Most days felt as if I was drinking out of a fire hose, but I had been around just long enough that I was starting to get the hang of things.

My flight lead and I had performed several sets of BFM prior to this. Much like a round of martial arts, we would fight until there was a clear winner then knock it off and reset. We were almost out of fuel but had just enough jet-A left for one more quick round of fighting. “Three-two-one, fight’s on!” I shoved the throttles to max afterburner, unleashing forty-four thousand pounds of thrust. I pointed the jet towards my opponent a couple miles away and attempted to use my Joint Helmet Mounted Cuing System, JHMCS, to train my radar on his jet to get off a simulated missile. Within a few seconds, our jets blasted by one another in a high-speed merge, like a couple of knights in a jousting match. With my jet partially inverted, I decided to continue my nose low dive towards the ocean in a split-S maneuver to bring my jet back around for another shot. With the control stick pulled all the way back into my lap, my jet was pulling seven and a half G’s. The jet rumbled as it tore through the air leaving vapor trails tumbling off the wings as it ripped through the sky. With a combined twenty pounds of head and helmet atop my head at nearly eight G’s, it felt like roughly one-hundred and sixty pounds as I strained my neck to look out the bubble canopy for the other jet. As I spotted my opponent and attempted another shot, I felt the jet ease its turn to only about four G’s. The stick was still pulled all the way back in my lap, but the jet was no longer doing what I wanted it to. It was like going around a sharp corner in a sports car then having the steering wheel kick back halfway. Instead of skidding off the road I was now stuck in a dive at the Atlantic Ocean.

Within a few seconds I had gone from over two miles above the ocean to only a couple thousand feet. At fifty-one degrees, nose low, in a steep dive, I was about to crash as the ocean rushed up at me. I pulled the black and yellow ejection handle between my legs and braced for impact. The ejection sequence takes less than a half second. Traveling at six-hundred-ninety-five miles per hour or ninety-five percent the speed of sound, my body violently impacted the transonic sound barrier like a rag doll. A normal ejection will permanently compress one’s spine and often causes a variety of flail injuries. This was the fastest survived ejection in the history of naval aviation. If you have ever stuck your arm out a car window going seventy miles per hour, you have felt about one one-hundredth the force that impacted my body.

Impacting the sound barrier ripped off my helmet and gave me a severe traumatic brain injury (TBI), a broken neck, and a broken left shoulder. Both my arms flailed violently and fractured in several locations as the gear on my survival vest ripped off and my dry suit shredded. The humerus bone in my right upper arm fractured and the broken fragments tore through my brachial artery causing internal bleeding. My brown steel toed boots turned into a couple maces as my legs smashed into one another leaving my tibiae and fibulas shattered in open fractures. Chunks of my bone and muscle tissue chummed the water. My parachute opened just enough to keep me from dying on impact with the icy Atlantic. I plunged into the open ocean and the parachute that just saved my life was pulled beneath the swell and the strong currents started to pull me under. At only thirty-seven degrees Fahrenheit the water felt like needles on my skin. As my head was pulled under, I felt painful brain freeze. The small explosive devices called SEAWARS that connected my parachute risers to my harness malfunctioned. The parachute did not disconnect as designed. With destroyed arms I was unable to disconnect manually.

For the next hour and a half, I was at the mercy of the frigid rough ocean as I was repeatedly pulled beneath the surface while my flight-lead heroically coordinated a rescue effort with almost no fuel to spare. Fortunately, my life preserver unit (LPU) had automatically inflated and provided just enough buoyancy to allow me to gulp a breath of air on occasion. If you have ever been held under by a big wave when you desperately need a breath of air, you know the feeling. I inhaled salt water into my lungs and was in and out of consciousness. With rapid blood loss I feared the massive white shark Mary Lee could come and finish me off at any second.

A Navy H-60 Seahawk helicopter from HSC-28 arrived on scene and spotted me. Rescue swimmer, Cheech, jumped in once the pilot maneuvered directly over me. Cheech clipped into the titanium D-ring on my harness and the current violently pulled us both under. Cheech said he was used to being pulled under during training and seeing the bottom of the brightly lit pool. When we were pulled under Cheech glanced into the dark blue bottomless abyss below as his training immediately kicked in. He was able to cut us free from the web of tangled paracord and pulled us both to the surface. We rode up the swinging, spinning line into the helicopter while being pelted with prop wash then headed straight for Norfolk General’s level one trauma center. The ride was only about forty minutes, but Cheech said it felt like it took five hours as they battled to resuscitate me repeatedly.

Once at the emergency room, they took my core body temperature. I was only eighty-seven degrees Fahrenheit. I should have been dead from hypothermia however the cold water kept me from bleeding to death. Had my dry suit functioned properly I would have bled to death long before anyone arrived. I was put on dialysis to aid my failing kidneys. My lungs were drained. I was put into an induced coma and underwent over a dozen surgeries over the next week. My skeleton was rebuilt with titanium rods and steel plates. Now my X-rays look like wolverine with all the metal bones. I had fasciotomies performed on all four extremities and had a vein graft on my brachial artery just before the surgeons nearly amputated my right arm. Had it not been for the surgical dream team, I would have been a quadriplegic, had I survived at all.

After another week in a non-induced coma, my family and squadron mates wondered if I was ever going to wake up. Things were depressing in the waiting room when my squadron mate Basil said, “He’s a scrappy mother fucker. He will be ok!” This helped to lighten the mood a bit and my callsign SMurF was born as a makeshift acronym for Scrappy Mother Fucker. Because of attempts to make us a kinder, gentler military, there must be a politically correct cover story for callsigns. The clever gents of the Pukin’ Dogs came up with the cover story that SMurF was my callsign because I am a short guy that turned blue from hypothermia.

After two weeks I woke up completely confused. I thought the thin wool blanket over me was made of lead as I could not budge it. I was paralyzed. The doctors told me I would never walk again or use my arms. My flying career was over. Something inside me wanted to prove them wrong. I spent the next three months as an inpatient doing full time therapy. I was eventually able to walk again with a walker and was able to get out of the VA polytrauma center in Richmond Virginia. The food and sleep there were less than ideal. I was hooked on over a dozen pharmaceutical drugs but at least I was alive.

Once out, I spent the next year and a half in full time outpatient therapy. I struggled through surfing with friends and even did some downhill mountain biking while barely able to use the brakes. I underwent several more surgeries and weaned myself off the pain meds, against the advice of the pain management clinic. The withdrawals were miserable. To everyone’s surprise I was eventually able to max out the navy physical fitness test. I returned to flying Super Hornets. I completed retraining in the Super Hornet at VFA-106 then was stationed with VFA-136 Knighthawks. I thought I had overcome it all until I started to suffer from insomnia, memory loss, and a variety of other mental impairments. I was given a diagnosis of delayed onset PTSD and was, once again, pumped full of pharmaceutical drugs. Before long it looked like my flying career might really be over.

I spent two years fighting through a medical board as the medication that was supposed to be helping me sleep, Quetiapine, started to cause psychosis. I was unable to distinguish between reality and my imagination. Life became a living nightmare, as my paranoia and hyper-vigilance transformed into intense visual and auditory hallucinations. Once eventually medically retired, I moved back to Northern Michigan with my wife and newborn son. One night I was ready to put my pistol in my mouth. I wondered what the gun oil would taste like and how the barrel would feel on my teeth. The only thing that stopped me was looking over and seeing my young son sleeping beside my beautiful wife. I did not want to wake them up.

Within a few days of having my evening dose of Quetiapine increased from three-hundred milligrams to four-hundred and fifty milligrams per night, I went into the most violent psychosis yet. My wife found me rustling around the house. I had shaved off most of my hair in chunks including my eyebrows. I was completely naked except for a black plastic garbage bag tied around my neck like a cape. I was about to go fight crime in the snowy Michigan winter. My wife rushed me to the emergency room. When my mom visited, she said I was feeding crumbs to a monster I thought lived behind the wall. I had the TV on a channel that was nothing but static and kept looking up at her with an eerie grin and, in fast-paced, staccato speech, I was saying, “Do you see that? Do you see that!? DO YOU SEE THAT!?”. In my mind I was able to change the channel and see into a dystopian future. The more I changed the channel, the further into the future I could see. It was devastating for my mom to see her once thriving son now captured by madness in a plexiglass room.

I was moved down to the Battle Creek VA inpatient acute care psych facility by ambulance. There I was given more medications and terrible food, and I was woken up every fifteen minutes to make sure I was “safe”. It got so bad in there I planned an escape using the fire alarm. When that failed, I was injected with Haldol, which made me want to tear off my own skin. While in a drug induced groggy state, a soulless lawyer got me to sign paperwork to deem me mentally defective legally. I am now no longer allowed to purchase a firearm and remain on the law enforcement information as though I’ve committed a felony. I have never been violent or committed a crime. I was just an American veteran trying to get some help. Instead, I was drugged and stripped of my constitutional rights.

Eventually my family got me out of the VA psych ward and back home. It took nearly six more months to come out of that psychosis. With real home cooked food, sleep and extra time outside playing with my son, I started to improve somewhat. My psychiatrist at the VA assured me the best option was to continue a high dose of Quetiapine. That drug made me lose all positive emotions. I became increasingly bitter, short tempered and depressed. I remember feeling ashamed when I yelled at my little boy, who was just trying to play with me. Just washing the dishes was overwhelming. I knew I needed something different to heal. I was only getting worse.

While most days I could not read more than a paragraph before forgetting what I had just read, I tried to absorb what I could as I researched alternative options. Psychedelic therapy caught my attention. I signed up for a guided psilocybin retreat, and in one evening I reconnected to the world around me. It was like a fresh snowfall over the rutted tracks of my negative emotions and behaviors. With the fresh powder in place, I was able to ride new lines and get out of my habitual state of misery. I recognized that as my dosage of Quetiapine increased over the years, my condition had worsened. Against the strong advice from my VA psychiatrist and my worried family, I weaned myself off Quetiapine. It was an unpleasant withdrawal over several months that caused insomnia and anxiety initially. I started to feel positive emotion again and I regained more of my focus and memory.

As I improved, I attended a running event in Texas called The Warrior Angels Foundation 4x4x48 challenge. From the mind of Navy SEAL David Goggin’s, we ran four miles every four hours for forty-eight hours straight. There, I was welcomed into a community of incredible veterans with similar experiences to mine. We had all been made far worse by pharmaceutical drugs following brain injury. As we completed the forty-eight-mile run, I had a renewed sense of purpose in life. Surrounded by incredible human beings with a shared mission to heal ourselves and others, I was rejuvenated. For the first time in a long time, I had hope. At the event I met Jesse Gould from Heroic Hearts Project. I was also given access to a variety of modalities including Nutraceuticals and extensive blood testing to find out what was wrong at a physiologic level. I was finally getting real help.

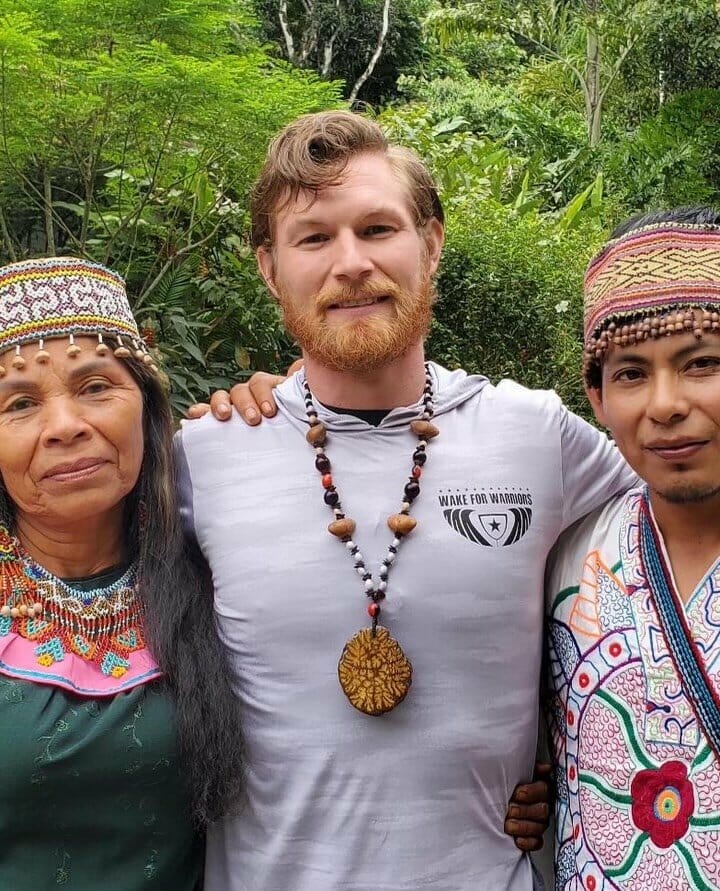

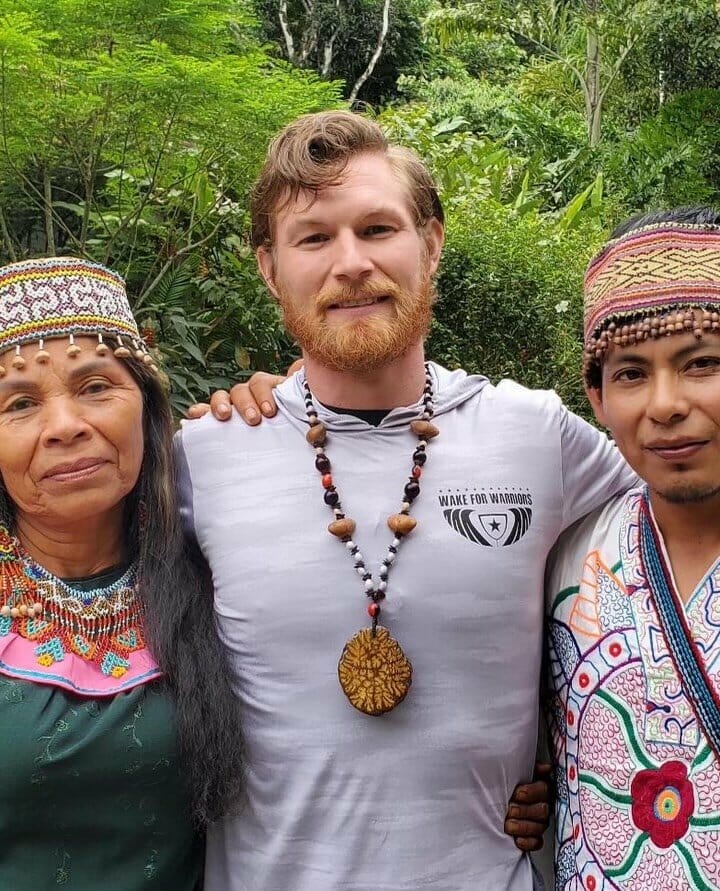

Since that turning point, my life has been on an upward trajectory. After eight and a half years of ineffective TBI treatment, I am finally healing my brain and soul properly. Heroic Hearts Project founder, Jesse Gould, invited me down to the beautiful Soltara Healing Center in Tarapoto, Peru, where I underwent three nights of intense ayahuasca ceremony. Under the guidance of two indigenous Shipibo shaman from the Amazon, seven other veterans and I essentially had surgery performed on our souls under the canopy of the rainforest. The first night was like an introduction to the medicine for me. The Shipibo make ayahuasca by combining bark from the spiral-like black ayahuasca vine with chacruna, a bush common in the rainforest. The two plants are mixed at a three to one ratio in a cauldron of water and cooked down for eight hours over fire. After drinking a shot glass full of the bitter potent mixture, I sat in the circle waiting for the thick dark medicine to take effect while smoking hand rolled mapacho tobacco.

After roughly an hour with almost no effect, the Shipibo shaman approached me. Immediately after the shaman started singing and directing spiritual energy into me, I snapped into visual hallucinations of fractals and patterns as the room spun. I felt nauseous and weak, as if I had been bitten by a venomous snake. I imagined a giant anaconda had swallowed me. I was inside the massive snake stomach while being slowly digested as the venom spread. Somehow, this became pleasant. It was as if the anaconda was caressing me. Calls of the countless late-night insects and amphibians overwhelmed the surroundings and influenced my hallucinations. After several hours, a shaman blew a ceremonial perfume at me. As I felt it splatter, I could see its odor impact my skin in red spinning spirals that looked like red and white peppermints. I immediately purged into my puke bucket. Fortunately, the Shipibo take purging as a complement. I got the impression that ayahuasca was giving me an introduction to what it was capable of, and the real experience was still to come.

After the first night’s ceremony closed, I stumbled back to my room. Before bed I puked one last time. As I purged, I saw a dark, veiny, muscular, deformed entity exit my body and dissolve in the toilet. I felt like something evil that had been trapped within me for a long time finally was gone. My nausea dissipated, and I laid down in bed. Despite the relief, my mind was too busy to sleep as I watched the sunrise peacefully.

We spent most of the next day eating the best produce I had ever had. The plants grown in the rainforest soil were so nutrient rich and fresh that the salad did not need dressing. It was naturally flavorful, tender and moist. After each meal, I felt completely satisfied despite the meals being a fraction of what I normally consume. Mid-day, the Shipibo bathed each veteran in an incredibly wonderful smelling flower bath. Our group had bonded as if we had known each other for years as we explored the jungle.

The second night’s ceremony started just after sunset once again. I took the same amount of ayahuasca as I had the first night. This time I did not feel nauseous. The room was completely silent and dark, with the occasional orange glow of the mapacho cigarettes some of us were calmly smoking. I began to hallucinate, and the room spiraled around me. I could see the counterclockwise flow of the room as if it were water. I then went into a very dark and terrible place. I could hear yelling and vomiting and felt like the people around me were being tortured. I was chained in an endless blackness in what felt like hell. The more I tried to resist, the tighter it squeezed me. I left my body, and time no longer existed. After what felt like years in hell, I started to spin into insanity. The more I tried to use logic and reason, the more insane I went. I was trapped paralyzed in a horrific loop. It beat me into submission. Once I finally let go of control I was rewarded.

My spirit elevated from the darkness. I experienced countless lives as insects, frogs, humans and a wide variety of other organisms. I experienced an entire lifetime as an old growth Amazon tree. In what felt like one breath as a tree, many generations of human civilizations grew and collapsed in front of me. I then became the spirit of the earth and gained a new perspective on time. I continued to become the sun, then the Milky Way galaxy, and finally, the universe. In several hours it felt like I had experienced eons. Each breath was like a life cycle. As I breathed in new life was born and grew. Holding my breath in was bright at first, and then would become sterile and begin to die. I would exhale, and things turned to a peaceful darkness. As I breathed in, the cycle began again, as I experienced the full spectrum of emotions throughout one full breath. It was like I was starting to understand the Ying and the Yang, light and dark and how it is all part of the same thing. I was being shown what God is in a way that I could make sense of with the limited capabilities of my human brain. I felt the interconnection between everything. How we are all made of the same thing and are connected in ways our simple five senses can not perceive.

My third eye was now open. I could see the energy that interconnects us and everything in the universe, multiverse and throughout all dimensions. Ayahuasca allowed me to reach a lucid dream-like state where I could control my experience. I could go anywhere and experience life as anything and everything, at will. I was God, as we all are. There is far more to my experience that night than I can articulate in words. As I started to return to this realm of existence, I took one last stop. I was in a room of other spirits. We had each been around since the beginning of time and communicated what we had each experienced and where we see the future going. We were not communicating with words but in some strange form of song and sounds. Somehow, I understood. I suspect the spirits I sat with were the spirits of the veterans in the room with me that night.

Once back in my human body and in this realm of existence, I came to in the stillness of the room. The ceremony was over, and the room was a mess. A lot of transformation had taken place that night. While I did not vomit that night several others had done so and more. Purging takes many forms including vomiting, pooping, peeing, sweating, crying and laughing. The wise gentleman who ran the retreat center joked that if you poop and vomit at the same time, it was called a double platinum. Someone had gone quadruple platinum that night by the looks and smell of things.

The final night I largely remained in a lucid dreamlike state where I could go where I wanted. I visited family and friends. I experienced what it was like for my parents when they had to deal with me stuck in a coma, post-ejection, wondering if I was going to live. The feeling of losing one’s own child made me cry, but I felt more connected to them by sharing that experience. I then felt as if the spirit of a black jaguar merged with my spirit. I felt the power of the muscular cat as I dug my claws into a tree and stretched my sore shoulder and back. The jaguar showed me how it could heal after being injured. I spent most of the remainder of the ceremony doing yoga as a jaguar.

The next day we shared our experiences with one another like knights of the round table. The owner of the retreat center was very experienced with ayahuasca and incredibly wise. Before we departed, he said something that stuck with me, “We are spiritual beings having a human experience.” The ayahuasca and Shipibo guides helped to heal my broken soul. Since Peru, my life has been flowing like breath. I am no longer clawing to survive.

Following the Ayahuasca retreat an incredible combat veteran named Kelsi Sheren put me in contact with Donna Cranston from Defenders of Freedom. Donna invited me to Dallas for a two-week brain clinic at Resiliency Brain Clinic. I was given access to a wide variety of modalities to heal my TBI. Many of these modalities are being intentionally suppressed by the pharmaceutical industry, as they pose a threat to their existing business model. If people truly heal, they no longer need pharmaceutical drugs. Had I received these treatments when I first started having problems from my TBI, I would likely still be flying Super Hornets.

It has been a year since I weaned myself off the antipsychotic, Quetiapine. I am now starting to thrive versus simply surviving. Please know that there is hope out there, and as more veterans heal, we can get back to fighting to help those struggling around us. We can become a beacon of hope for others and truly help repair our country and the world. First, we must heal ourselves.