Legalizing Psychedelics as Therapeutic Medicine

The 2020 election season was historic in a number of ways. When it comes to psychedelics we saw Oregon pass a measure to legalize administration of psilocybin and become the first state to decriminalize all drugs. The District of Columbia passed a measure to make the investigations and arrests related to entheogenic plants and fungi one of law enforcement’s lowest priorities. With the passage of these two historic measures does this mean we are finally on the road to nation-wide legalization of psychedelics?

From xenophobia to taxes: the path to recreational marijuana

One way to examine the path to legalization of psychedelics is to look at the journey marijuana has made over the last two centuries. In the late 1800s, marijuana was a popular ingredient sold openly in American pharmacies, alongside cocaine and other opiates. However, American usage of marijuana was limited to hashish and other preparations. Smoking of the plant was introduced to Americans by Mexican immigrants who came over after the Mexican Revolution of 1910 and the drug became associated with the Spanish speaking newcomers. Growing resentment and fear of Mexican immigrants during the Great Depression fueled “research” that associated crime, violence and suicide with the use of marijuana by “racially inferior” groups and lower classes of society. By 1931, marijuana was outlawed in 29 states.

During the 60s and 70s, shifting cultural attitudes and a counterculture movement began to make marijuana widespread among college students and the white upper middle class. Simultaneously, President Nixon who ran on a platform to restore “law and order” took a very anti-marijuana stance. In 1973, the bipartisan Shafer Commission, appointed by President Nixon, reviewed marijuana laws determining that personal use should be decriminalized and that anti-drug education was a waste of money. Nixon rejected the committee’s findings but several states (Alaska, California, Colorado, Nebraska, New York, North Carolina, Maine, Minnesota, Ohio, and Oregon) used the committee’s recommendations to decriminalize marijuana possession in the 1970s.

During the 80s and 90s, American Presidents furthered the “war on drugs” by instituting more anti-drug campaigns in schools and on television. These programs did not distinguish between types of drugs, although federal sentencing requirements made some drugs worse than others. Although blacks smoked marijuana at an identical rate to whites, they were four times more likely to be arrested for it. This uneven application of the law in addition to the Schafer committee’s findings has called many to question whether the war on drugs was a racially motivated crusade.

In the 1990s, the AIDS epidemic as well as studies regarding relief for chemotherapy patients started to change people’s minds about the use of marijuana. By 1996, California passed Proposition 215 permitting the use of cannabis for medicinal use. As of November 2020, 35 states and 4 territories passed laws legalizing the use of medicinal marijuana. By 2014, Washington and Colorado legalized recreational marijuana use by adults. Since then, 15 states and 3 territories have followed suit. Many of these states levy significant taxes (ranging from 7-37%) on marijuana sales dedicating a portion of the revenue to state specific programs. In 2018, Colorado collected $267 million and Washington collected $439 million in state marijuana taxes.

The roadblock to legalization: the Controlled Substances Act

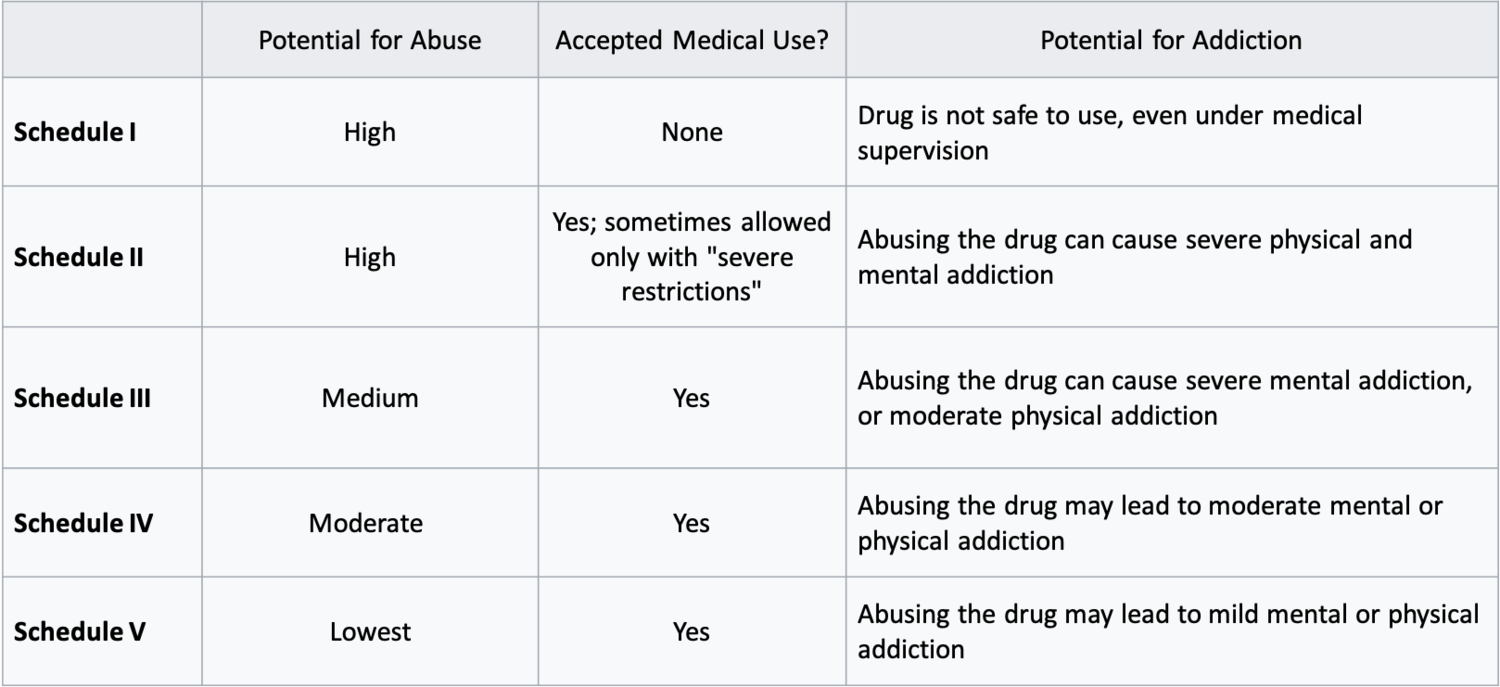

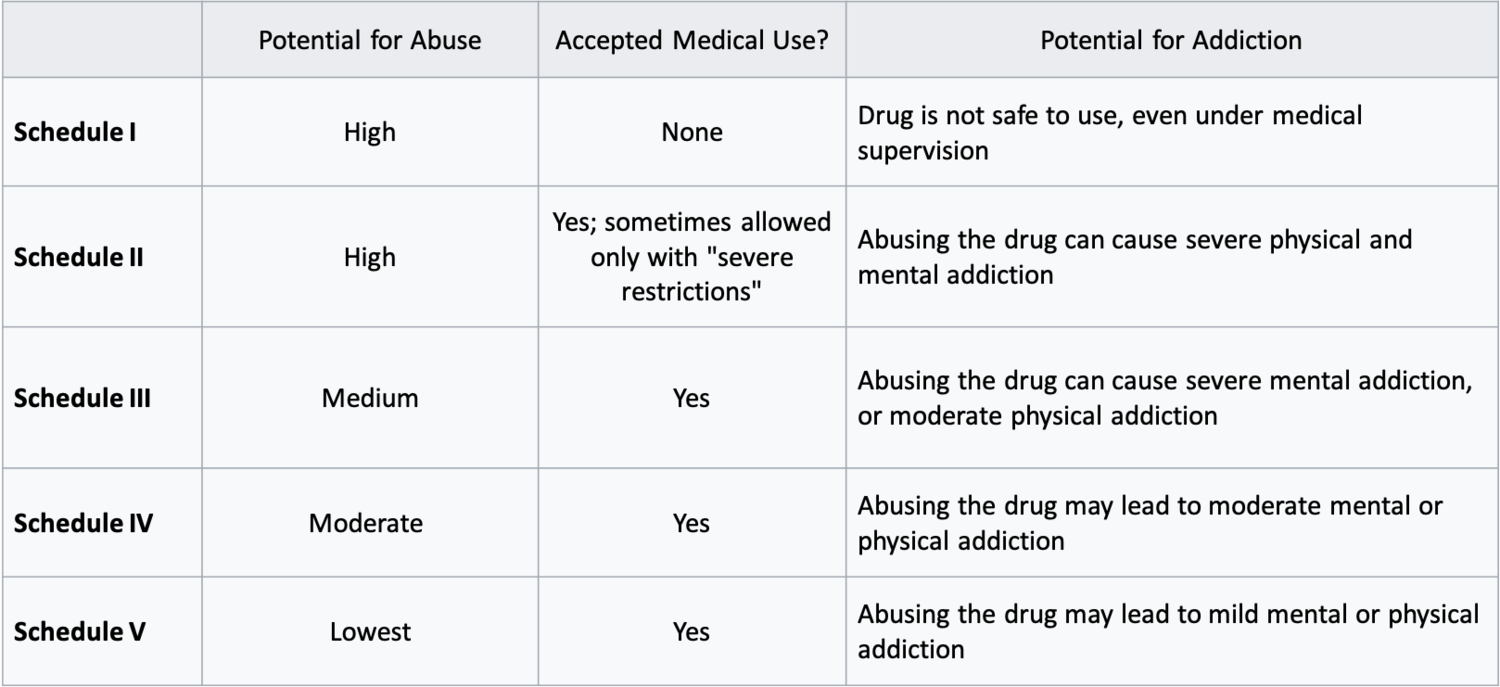

During the Nixon Administration, the Controlled Substances Act was passed. This legislation created five schedules under which all controlled substances would be assigned based on their potential to be addictive, abused, or have accepted medical usage. Schedule 1 drugs are the most restricted class and are deemed to have no medicinal purpose, a high potential for abuse, and lack of accepted safety under medical supervision. The following table reflects a summary of the other classifications.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Controlled_Substances_Act

Although the Schafer commission found that there was no need for marijuana to be placed on Schedule 1, Nixon demanded it be placed on the list where it still remains. Schedule 1 drugs also include heroin, lysergic acid diethyl-amide (LSD), MDMA (ecstasy), methaqualone (quaaludes), peyote, DMT (active ingredient in ayahuasca), and psilocybin (active ingredient in mushrooms). According to federal law, prescriptions cannot be written for schedule 1 drugs. Schedule 2 drugs include cocaine, oxycodone, and fentanyl. “Schedule 1 and 2 drugs face the strictest regulations. Schedule 1 drugs are effectively illegal for anything outside of research, and schedule 2 drugs can be used for limited medical purposes with the DEA’s approval — for example, through a license for prescriptions.” (vox.com)

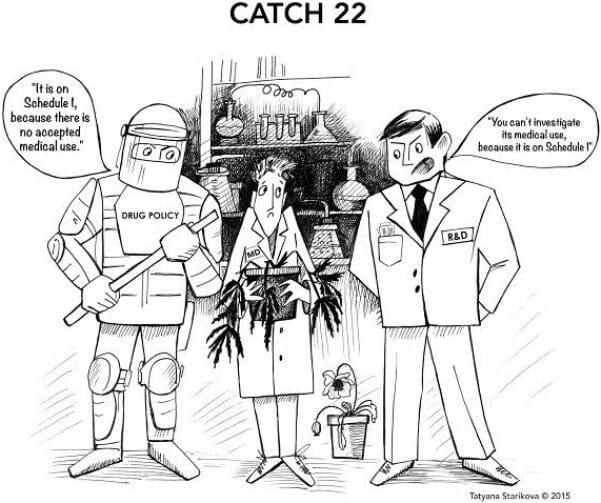

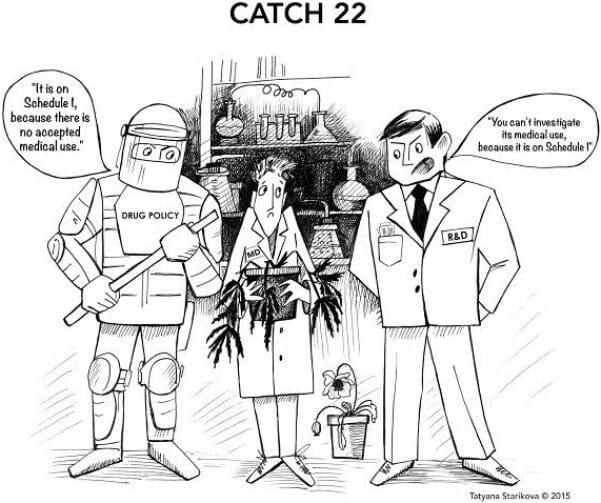

The catch-22 of this style of regulation is simply put: there is little evidence of the therapeutic effects of controlled substances because there are few studies. There are few studies, because of regulations that consider these drugs to have no medical benefit.

This catch-22 presents significant barriers to research. Social attitudes, ethical concerns and fears of legal prosecution, addiction, and reputation limit many researchers, institutions, Institutional Research Boards, and funding agencies from pursuing research on schedule 1 and 2 drugs.

Furthermore, the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) establishes and limits the amount of Schedule 1 and 2 drugs that are available for research. Due to these limitations, the amounts that would be needed for wide scale clinical trials aren’t readily available furthering research restrictions. In order for a drug to be reclassified, Congress could pass a law. More realistically, the US Attorney General’s office could initiate a review, examining available evidence to change a drug’s classification. Adjusting the classification of many of these substances would go a long way to de-stigmatizing their implications and opening the road for more research and perhaps even a path to nationwide decriminalization.

Looking towards the future of psychedelics

As we saw with marijuana, in order for psychedelics to become legal, several things need to happen. Changing cultural attitudes, like those brought on by shifting norms in the 60s and 70s, paved the way for states to pursue decriminalization and decriminalization paved the way for additional research. We are now seeing states conduct their own studies based on their patients’ experiences with marijuana treatment. And the results have been promising.

Eventually, States may begin to realize the financial benefit associated with regulation of psychedelics but the constant clash between federal and state drug policies will need to be resolved. Perhaps the next administration will take up the fight to start remedying the arbitrary and antiquated drug classification system to allow better access to research of psychedelics as therapeutic medicines.

Recent laws in Oregon and DC, reflect the changing attitudes among voters. Decriminalization laws and ordinances have been passed in several cities around the United States including Denver, Oakland, and Chicago. It took 40 years for California to go from decriminalizing marijuana to allowing for recreational use. Hopefully, the fight for psychedelics won’t be as long. As the famous Chinese proverb says, “the journey of 1,000 miles begins with a single step.” Even though the path to legalization, or even declassification isn’t guaranteed or clear, these small steps bring us closer to unlocking the therapeutic potential of psychedelic drugs for all Americans.

Sources

Ballotpedia: Oregon 2020 ballot measures

Ballotpedia: Washington DC 2020 local ballot measures

List of Enthnogenic Plants and Fungi

Slate: Which States Have Decriminalized Marijuana Possession?

Previous Post

How Does Ayahuasca Impact the Brain?